Root resistance to attacks by pathogenic agents

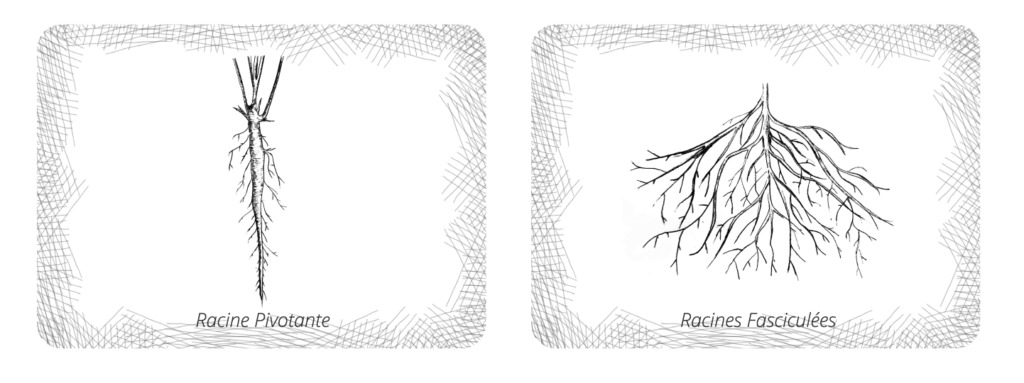

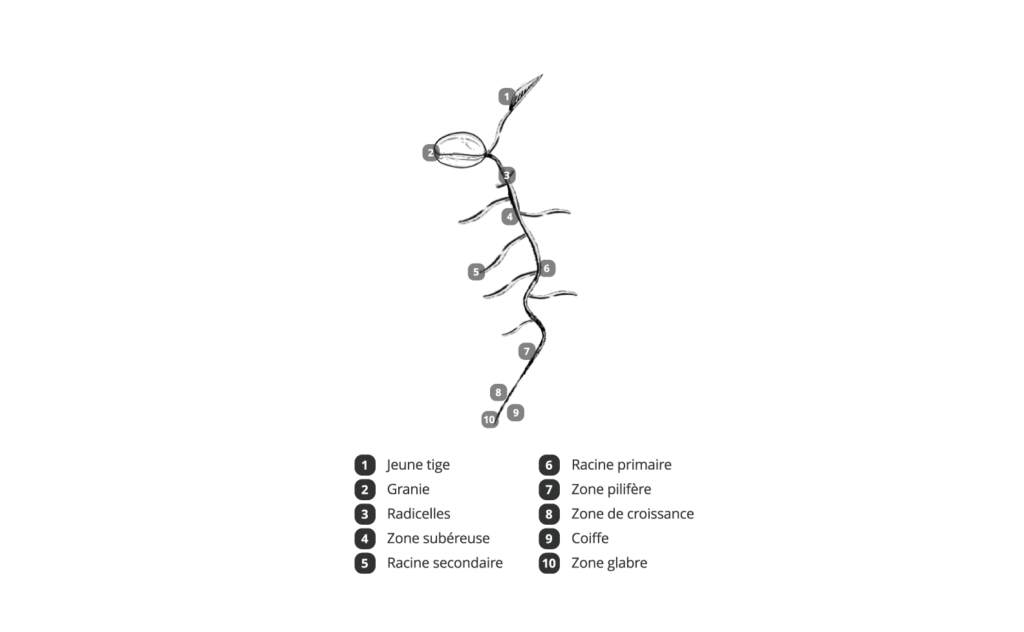

Because the roots are hidden under the surface of the soil, it is often forgotten that they greatly contribute to obtaining attractive yields. There are different types of root systems. The 2 main root systems are taproot or fibrous. The taproot root system is found especially in dicotyledons and gymnosperms. It is characterized by a main root which sinks vertically into the ground, and on which lateral secondary roots develop. This allows particularly effective anchoring for decompacting the soil. A taproot can also be tuberized: radish, carrot, beet, potato. Observed in many monocots, the fibrous root system forms a beam: the roots all start at the same point, and there is not the predominance of a main root. Examples are grasses, corn and bulbous plants. The roots appear from a tray.

Pathogens such as fungi and nematodes damage roots and reduce their ability to take up fertilizers efficiently, leaving more leaf space above ground for weeds to take advantage of. Environmental factors such as excess water, soil texture that is too compact or even frost can trigger attacks by pathogens on the roots. When they affect cultivated plants, diseases can have serious economic consequences. This is for example the case of peas because of the pathogenic fungus Aphanomyces Euteiches causing considerable root damage.

Anchoring in the soil and nutrition are far from being the only functions of roots! Long ignored, the defense mechanisms put in place by these organs, particularly at the level of the root cap, have given rise to numerous studies over the past ten years. In regular growth, the end of the root with the meristem is a vulnerable zone, since the conductive vessels there are not yet mature (non-lignified) and therefore more permeable to vascular pathogens which can make use of this portal entry to colonize the rest of the plant. This latter has therefore put in place various mechanisms to protect this area.

The bordering cells form a “tissue” in their own right comprising cells isolated from each other and included in a thick mucilage. In addition to being a mechanical protection, they intervene actively in the defense by secreting compounds of low molecular weight, the phytoanticipins which act as a chemical barrier against a wide range of aggressors (bacteria, insects, nematodes, fungi). When the plant is attacked, it will strengthen its defenses by increasing the production of phytoanticipins and by synthesizing other low molecular weight antimicrobial compounds called phytoalexins. Among defense exudates, phenolic compounds and terpenoids, in particular, have high antibacterial and antifungal capacities.

Resulting from the desquamation of the cap, these cells undergo a significant modification in the expression of their genes and begin to secrete repellent, inhibitor or biocide compounds. Phytohormones such as auxins and cytokinins must then be activated to regenerate plant cells exhausted by these defense mechanisms. Phytohormones are naturally present in plants in quantities of the order of micrograms per litre. Auxins are responsible for:

- Cell elongation.

- Stimulation of mitosis (cell division of a mother cell into two daughter cells).

- Rhizogenesis (root formation). Auxin has a strong rooting power, when a root fragment is placed in a medium containing auxin, the appearance of lateral roots can be observed.

Cytokinins: Produced mainly in the roots, they circulate throughout the plant through the raw sap through the xylem. They complement the action of auxin in cell elongation by acting in the organs where the latter does not act (tuber in particular). Depending on their respective concentration, the simultaneous use of auxin and cytokinin will induce different responses:

- If the auxin/cytokinin ratio is high, root formation is favored.

- If the auxin/cytokinin ratio is low, the formation of buds is favored.

It is recommended to visit its plots as soon as the seedlings start to emerge from the ground and then every week for a month. Place the washed seedlings on a white paper towel and blot excess water with another paper towel. Generally, healthy roots are white and well developed with secondary roots and rootlets. Diseased roots may show spots or brown patches. Sometimes they are truncated and the tip is dark brown. You should also observe the collar. In some cases, the disease is concentrated in the collar. There is a wide variability of symptoms. In the case of cereals, it may be possible to determine the origin of the inoculum, either from the soil or from the seed. When the rhizome (the part that comes out of the seed and goes up to the collar) or the seminal roots (the first roots that come out of the seed) are browned or rotten, the pathogenic fungus is probably coming from the seed. When it is the ends of the roots that are brown and rotten and the parts near the seed are healthy, then one can suspect an inoculum coming from the soil. Here are some obvious signs of pathogen attacks:

- The plants are dead and show no lesions on the foliage.

- The base of the plants shows yellowed leaves.

- The presence of smaller or pale green plants per area in the field.

Here are some subtle clues of pathogen attacks:

- Germination is slow or non-existent.

- The plants seem to lack fertilizer or water.

Very dry sowing conditions followed by cooler temperatures and heavy rains favoring excess water in the fields are conducive to Pythium infections. The latter detect the rootlets that begin to emerge from the seeds and attack them quickly. During hot and dry springs, cereals sown on light or sandy soils are more susceptible to attack by Fusarium present in the seeds and in the soil. The roots may show brown lesions or be completely rotten.